Fire Weather

The wildfires in California replicate the massive fire storms in the boreal forest in Canada and Siberia, the lungs of the earth. Our addiction to fossil fuel has ignited an age of fire.

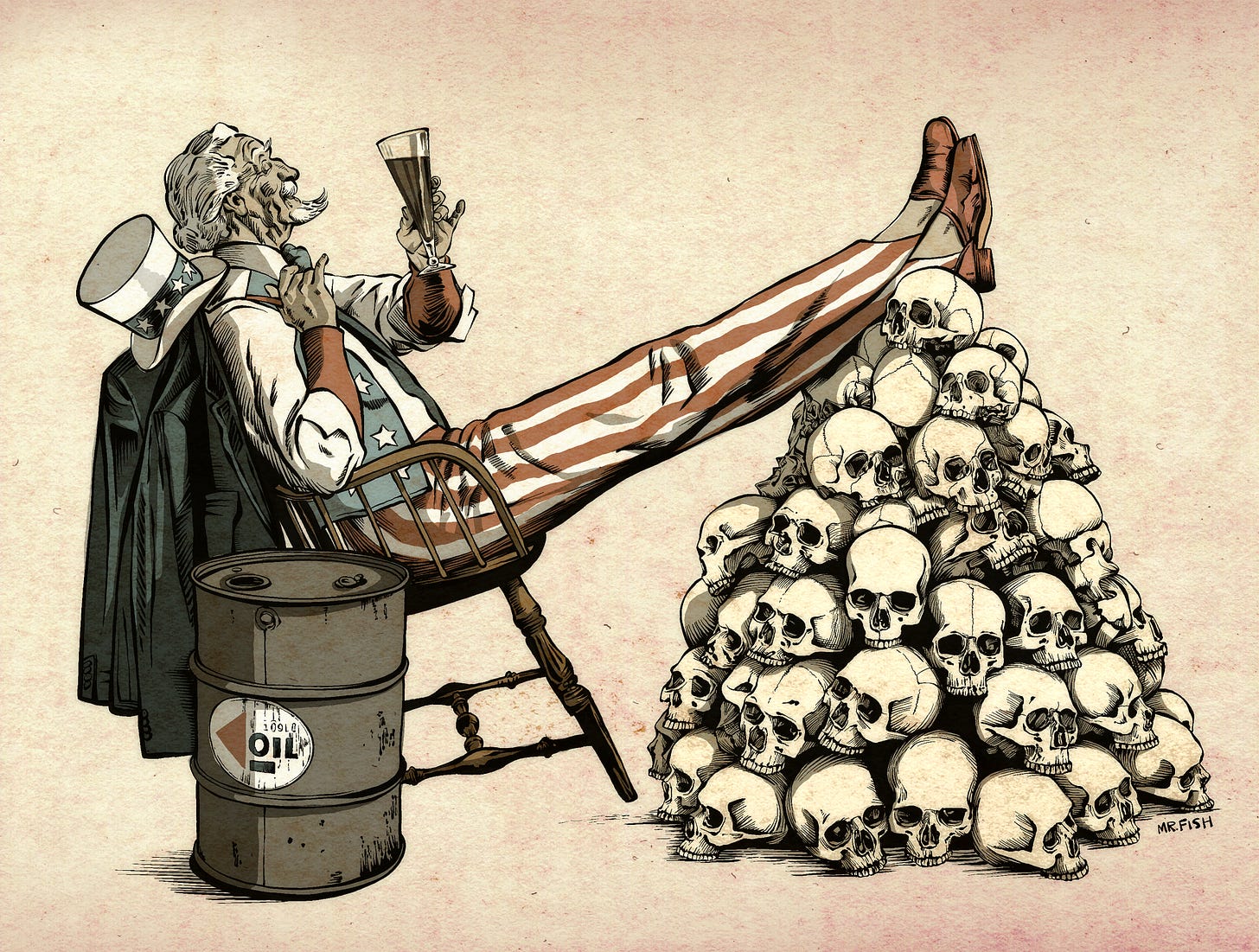

A Final Toast - by Mr. Fish

The apocalyptic wildfires that have erupted in the boreal forest in Siberia, the Russian Far East and Canada, climate scientists repeatedly warned, would inevitably move southwards as rising global temperatures created hotter, more fire-prone landscapes. Now they have. The failures in California, where Los Angeles has had no significant rainfall in eight months, are not only failures of preparedness — the mayor of Los Angeles, Karen Bass, decreased funds for the fire department by $17 million — but a failure globally to halt the extraction of fossil fuel. The only surprise is that we are surprised. Welcome to the age of the “Pyrocene” where cities burn and water does not come out of the hydrants.

The boreal forest is the largest forest system on earth. It circumnavigates the Northern Hemisphere. It stretches across Canada and Alaska. It travels through Russia where it is known as “the taiga.” It reaches into Scandinavia, picks up again in Iceland and Newfoundland, and moves westward across Canada, completing the circle. The boreal forest has more sources of freshwater than any other biome, including the Amazon Rainforest. It is the lungs of the earth, able to store 208 billion tons of carbon, or 11 percent of the world’s total. Yet it has been steadily degraded, assaulted by deforestation and the extraction of the tar sands in Alberta, Canada — which produces 58 percent of Canada’s oil and is the U.S.’s largest source of imported oil — man-made drought and rising temperatures from carbon emissions.

Almost two million acres of boreal forest have been destroyed by extraction industries and timber companies. They have scraped away the topsoil and left behind poisoned wastelands. The production and consumption of one barrel of tar sands crude oil releases between 17 and 21 percent more carbon dioxide than the production and consumption of a standard barrel of oil. The oil is transported thousands of miles to refineries as far away as Houston, through pipelines and in tractor-trailer trucks or railroad cars.

This vast assault, perhaps the largest such project in the world, has accelerated the release of carbon emissions that, unchecked, will render the planet uninhabitable for humans and most other species. There is a direct line from the destruction of the boreal forest and the raging wildfires in California.

The boreal forest system has, for over a decade, seen some of the planet’s worst wildfires, including the 2016 Wood Buffalo (aka Fort McMurray) wildfire, which consumed nearly 1.5 million acres and which was not fully extinguished for 15 months. The monster wildfire, which was, according to journalist John Vaillant, about 950 degrees Fahrenheit — hotter than Venus — destroyed thousands of homes and forced the evacuation of 88,000 people. The fire ripped into Fort McMurray with such ferocity and speed that residents barely escaped in their cars as buildings and houses were instantly vaporized. Flames shot 300 feet into the air. Fireballs rolled up into the smoke column for another 1,000 feet. It was a harbinger of the new normal.

More than 100 climate scientists have called for a moratorium on the extraction of tar sands oil. Former NASA scientist James Hansen warned over a decade ago that if the tar sands oil is fully exploited, it will be “game over” for the planet. He has also called for the CEOs of fossil fuel companies to be tried for “high crimes against humanity and nature.”

It is hard to get a sense of the scale of the destruction unless you visit, as I did in 2019, the Alberta tar sands. I spent time with the 500 inhabitants of Beaver Lake, the Cree reserve, most of whom are impoverished and live in small, boxy prefabricated houses. They are victims of the latest iteration of colonial exploitation, one centered on the extraction of oil that is poisoning the water, soil and air around them.

Beaver Lake, as I wrote at the time, is surrounded by over 35,000 oil and natural gas wells and thousands of miles of pipelines, access roads and seismic lines. The area also contains the Cold Lake Air Weapons Range, which has appropriated huge tracts of traditional territory from the native inhabitants to test weapons. Giant processing plants, along with gargantuan extraction machines, including bucket wheelers that are over half a mile long and draglines that are several stories high, ravage hundreds of thousands of acres.

“These stygian centers of death belch sulfurous fumes, nonstop, and send fiery flares into the murky sky,” I wrote. “The air has a metallic taste. Outside the processing centers, there are vast toxic lakes known as tailings ponds, filled with billions of gallons of water and chemicals related to the oil extraction, including mercury and other heavy metals, carcinogenic hydrocarbons, arsenic and strychnine. The sludge from the tailings ponds is leaching into the Athabasca River, which flows into the Mackenzie, the largest river system in Canada.”

Nothing in this moonscape, by the end, will support life. “The migrating birds that alight at the tailings ponds die in huge numbers,” I noted. “So many birds have been killed that the Canadian government has ordered extraction companies to use noise cannons at some of the sites to scare away arriving flocks. Around these hellish lakes, there is a steady boom-boom-boom from the explosive devices.”

The water in much of northern Alberta is no longer safe for human consumption. Drinking water has to be trucked in for the Beaver Lake reserve. Cancer and respiratory diseases are rampant.

John Vaillant, author of “Fire Weather: On the Front Lines of a Burning World” describes the tars sands landscape:

…mile upon mile of black and ransacked earth pocked with stadium-swallowing pits and dead, discolored lakes guarded by scarecrows in cast-off rain gear and overseen by flaming stacks and fuming refineries, the whole laced together by circuit board mazes of dirt roads and piping, patrolled by building-sized machines that, enormous as they are, appear dwarfed by the wastelands they have made. The tailings ponds alone cover well over a hundred square miles and contain more than a quarter of a trillion gallons of contaminated water and effluent from the bitumen upgrading process. There is no place for this toxic sludge to go except into the soil, or the air, or, if one of the massive earthen dams should fail, into the Athabasca River. For decades, cancer rates have been abnormally high in the downstream community.

The out-of-control fire storms and blizzard of swirling embers, he chronicles, are what we are witnessing in California, a state which normally experiences wildfires during June, July, and August. Neighborhoods burn “to their foundations beneath a towering pyrocumulus cloud typically found over erupting volcanoes” and fires generate “hurricane-force winds and lightning that ignites fires miles away.”

These cyclone-like fires resemble the firebombing of Hamburg or Dresden during World War Two, rather than forest fires of the past. They are almost impossible to control.

You can see an interview I did with Vaillant here.

“Fire wants to climb,” Vaillan told me. “[W]e all know heat rises. It’s rising up into the treetops and it’s sucking in wind from underneath because it needs oxygen all the time. So the fire, it’s helpful to think of it as a breathing entity. It’s pulling oxygen in from all around and rising into the architecture of the trees and so there’s this rushing chimney-like effect. Where the fire is in a way happiest, most energetic, most charismatic, and dynamic is up in the treetops, and then it’s pulling in wind from down below. As that heat builds, as the whole tree is engaged, you have this increasing heat and increasing wind which then builds on itself so it becomes almost a self-perpetuation machine. If you have hot enough, dry enough, [and] windy enough conditions, those flames will then begin to leap from treetop to treetop.”

The heat releases vapor, hydrocarbons from the fuels around it, which is why we see “explosive fireballs and massive surges of flame coming out of big boreal fires because that’s the superheated vapor rising up and then ignited. Imagine an empty gas can — even though there might not be a lot of liquid in it, it will still explode in a spectacular fashion. Well, that’s really what the fire is enabling in the forest, for all those hydrocarbons to release in this gaseous cloud that then ignites. That’s when you see, especially a boreal fire, in full run. It’s called a Rank 6. It’s comparable to a Category 5 hurricane.”

When houses and buildings become very hot they, like trees, release hydrocarbons. Vaillant calls modern buildings “incendiary devices.” They are packed with petrochemicals and often sheathed with petroleum products like vinyl siding and tar shingles. When fires push temperatures to over 1,400 degrees the vinyl siding, tar shingles, glues and laminates in the plywood vaporize.

“The modern home is in fact more flammable than a log cabin or a 19th-century home that’s made mostly out of wood, mostly furnished with cotton-stuffed furniture or horse hair stuffed furniture, things that we think of as antiques now,” Vaillant said. “But the modern home is really in a way a giant gas can and we don’t think of that when it’s 75 degrees. But when it’s 300 degrees because of the radiant heat coming off a fire, or 1,000 degrees because of the radiant heat coming off a boreal wildfire, it turns into something completely different.”

“All of us alive today have grown up in the petroleum age,” Vaillant said. “It feels normal to us the way I think people smoking on airplanes and in doctors’ waiting rooms felt normal to people in the 1950s. We’re completely habituated to it, to the point that it’s invisible to us. But if you really stop and think about how petroleum is rendered and what it in fact is, it’s literally toxic at every stage of its life. From the moment it’s drawn from the ground through the incredibly polluting refining process, into our cars and where it’s burned…Petroleum will kill you in every form, whether as a liquid, as a toxic spill, as a gas, as an emission. It’s strange to think that we have surrounded ourselves and persuaded ourselves that this profoundly toxic substance is an ally to us and an enabler of this wonderful lifestyle that we live that is now being compromised in measurable and visible ways by that very energy source.”

We have harnessed the concentrated energy of 300 million years and set it alight. We are addicted to fossil fuels. But it is a suicide pact. We ignore the freakish weather patterns and disintegration of the planet, retreating into our electronic hallucinations, pretending the inevitable is not inevitable. This vast cognitive dissonance, fed to us by mass culture, makes us the most self-deluded population in human history. The cost of this self-delusion will be mass death. The devastation in California is the harbinger of the apocalypse.

I suspect that our fire weather is connected to the billions of dollars we are spending on armaments that we send all over the world. All those bombs are releasing carbon and other pollutants into the atmosphere, so we continue to cause destruction. In a sense, the bombs are exploding in Los Angeles, as well as Gaza and Ukraine and Yemen and…

How does warfare compare with our use of fossil fuels and its effect on our climate?

Chris, your post brought to mind Noam Chomsky and his extensive knowledge. While I miss hearing Professor Chomsky speak, I am grateful for your presence and the important work you do. I am deeply thankful to you and all those who tirelessly advocate for humanity.